India is the world’s biggest producer of cotton. In October, I participated in a study tour to see an Indian cotton farm organized by the non-governmental, non-profit organization ACE, which addresses the issue of child labor around the world.

I have seen for myself the problems that are deep-rooted in Indian society: health issues caused by pesticides, child labor, and caste disparities. There were many problems, but at the same time, I also met people who work against them.

GMOs and Pesticides

Currently, most of the cotton harvested in India is “conventional” cotton. Conventional cotton farming is different from that of organic in many ways. It typically treats seeds and weeds with fungicides or insecticides, and uses genetically modified seeds (GM seeds).

In 2010, when I visited the cotton farm in Texas, its farming was very intensive, using innovative techniques in agricultural machinery and farming methods on a large scale. Under this system, they need to spray defoliant from helicopters, so they had the problem that a massive amount of defoliant permeates their soil.

However, an Indian rural farm is an accumulation of small farm units owned by a family. They do not spray defoliates, but they still use a lot of toxic chemicals such as synthetic fertilizers, fungicides, and insecticides. Farmers work in a field filled with these chemicals without sufficient equipment. They have no other way to gain non-GM seeds. Moreover, when they buy GM seeds, they are required to purchase chemical treatments too. They are told they will get more crops and will be able to earn more money by using these treatments. The brokers also suggest loaning them money in advance for the payment of seeds. Since farmers have no savings, they jump at the chance. It is true that GM cotton grows taller and will have more cotton on the branch. But this means that they need to use more water and treatments.

Also, since Indian farms rely on rain for watering, the final harvest depends largely on weather. Therefore, many farmers come to find that they do not get that much money after all, and they are driven to suicide because of their debt. The Indian government provides condolence money when their people die from suicide. For fathers of the family, this condolence is a last way to pay the debts of their families.

Child Labor

Child labor is different from child work. Child labor is work that harms children or keeps them from attending school. In cacao farms, in coffee farms, in many places around the world, many children are forced to work under severe conditions. According to the ILO, one out of nine children (10.6%) is currently exposed to child labor (ILO, “Marking Progress against Child Labour,” 2013). India scores higher with one out of five children, and it is especially serious with conventional cotton farms, where many children are working, mainly doing tasks like pollination, with no chance to attend school.

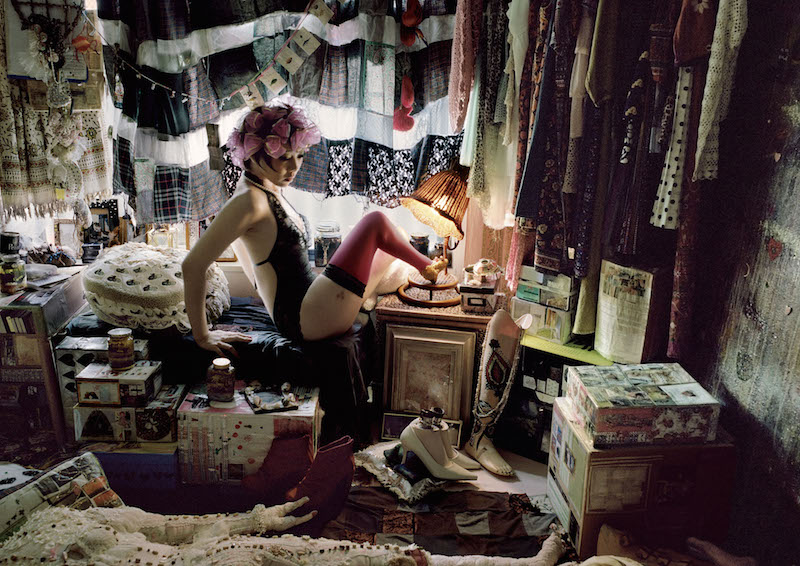

11 year-old girl, working in the cotton farm. She told me she actually wanted to attend school.

In this tour, I visited a town in the Mahbubnagar district, which successfully reduced the numbers of children exposed to child labor. Now, their lifestyle has greatly changed, and most of the children in this town are attending school. NGOs working in this area visited every family and patiently listened to their stories and problems. They convinced the parents to have their children attend school.

I too had the chance to listen to stories of children and their parents. Why did the parents prevent their child from going to school, which should be a natural expectation for parents in our society?

First, parents in this area had not attended school, so they were not sure of the purpose of an education. Second, their life is harsh. Their incomes are low, and the family needs as many members working as possible.

There were some children protesting for the right to go to school. However, if they were asked how they would earn a living without working, the children had no answer. Working in the fields exposed to chemicals is a cruel environment. Not a few children destroyed their health and lost their lives to illnesses like cancer.

I also had the chance to visit an elementary school. There, I was able to hear the stories of children who were previously child laborers. It impressed me a lot that many of the children were smiling and telling me that they are more than happy that they are now able to learn. They also told me that their parents do not tell them to work any longer, but to study more. Seeing children’s healthful and happy growth, it is clear that parents’ way of thinking is changing too.

Moving From Conventional to Organic

Now that they are aware of health threats from severe, insecure environments, some Indian people themselves are now trying to change the situation. And those people are trying to promote organic cotton, instead of conventional cotton harvesting. There are actually some companies that are successful in business too.

The transition to organic cotton harvesting is not as easy as merely talking about it. Companies need to spin the high motivation to harvest organic cotton, talk to every family in town about why they should be harvesting organic cotton, and convince them to do so by promising them that the company will buy their crop.

Farmers do understand the benefits for the transition; however, it is natural for them to be careful to change what they have been doing. They wouldn’t know how much they could harvest, without chemicals that they are familiar with and rely on. It requires patience for the members of the spinning company to explain and convince farmers to try organic cotton. But gradually, influenced by their passion, farmers start harvesting organic cotton.

In order to be officially certified as organic cotton, farmers must cultivate their soil without chemicals for at least three years. This period of time requires patience for farmers. Meanwhile, they practice farming methods for organic cotton and prepare for the coming chance to start real organic farming. We consumers must understand the difficulties and fears that farmers are overcoming.

The production of organic cotton is only 5% of overall cotton production in India. However, we need to continue to create successful cases to show the Indian people that organic cotton can be more helpful for them.

A girl formerly working at cotton farm. Now she attends to school, she shared how her life changed.

Making Choices as Consumers

Sometimes, my friends ask me why we should be choosing organic cotton. Japanese women have an especially high interest in skin care, and sometimes they ask me, “Is it good for our skin?” However, conventional cotton and organic cotton are no different by the time they become a product. Conventional cotton is washed numerous times during processing, and toxic chemicals do not last. How healthy or unhealthy it is for skin is relative, depending on the skin.

The real value of choosing organic cotton is not something superficial. It makes our soil healthy and prevents children from child labor. For me, encouraging these achievements is not a charity or something like “noblesse oblige.”

For example, I do not want use chemicals in my own garden. I do not want to pollute our earth, where my children and I are living. Our world is connected; I believe we have to pay for it someday, if we harm something, even if you don’t think you’re connected with it. I do not want to live in an unnatural environment, and I really want health for my child. So I wish for it as well, for other children on earth.

Choosing organic is not an immediate remedy, but I believe it is something that will make us happy. Happiness is passed on, from person to person. That is why I want to choose organic cotton.