Written By:Dr. Pamela Ravasio, Twitter: @PamelaRavasio, director of texSture.

Written By:Dr. Pamela Ravasio, Twitter: @PamelaRavasio, director of texSture.

Via:http://www.rapanuiclothing.com/ethical-fashion/traceability-clothing.html

Consumers are Suspicious about Social Cause Products Businesses

A recently published consumer study revealed that 52% of U.K., U.S., and Canadian consumers believe that businesses are half-hearted in their alignments with social or charitable causes; 88% of consumers are suspicious whether money donated to a particular cause actually goes where promised; and over 75% of consumers state that companies do not disclose enough information about how consumer and corporate funds are allocated to and benefit the charitable or social causes targeted.

In other words, consumers assume that green-washing is the rule rather than the exception. They have become outspoken cynics with regard to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the engagement of corporations in sustainable practices, and few consumers actually believe what is written in publicly available information, such as company and CSR reports. The attitude of consumers in regard to the fashion industry in particular comes as no surprise, specifically in view of a continued series of scandals, such as organic cotton mislabelling, toxic ‘organic’ cosmetics, and repeat labour malpractices to just name a few.

Consumers expect the behaviour and sustainability efforts of businesses to be integral to their business. Consumers expect the behaviour and sustainability efforts of businesses to be integral to their business. Commitment to sustainability merely to create public goodwill is clearly condemned by the public . But how can consumers distinguish pure intentions from intentions with ulterior motives? The key to businesses being credible in their aim to be green is not only mere adherence to regulations and standards, but also transparent communication of verifiable information. This request for transparency and publicly rendered accounts will no doubt cause raised eyebrows among both, multinationals but also small, locally rooted companies.

The question is of course: what tools other than, or in addition to, legislation, certifications and consumer labels does the fashion industry have to provide transparency?

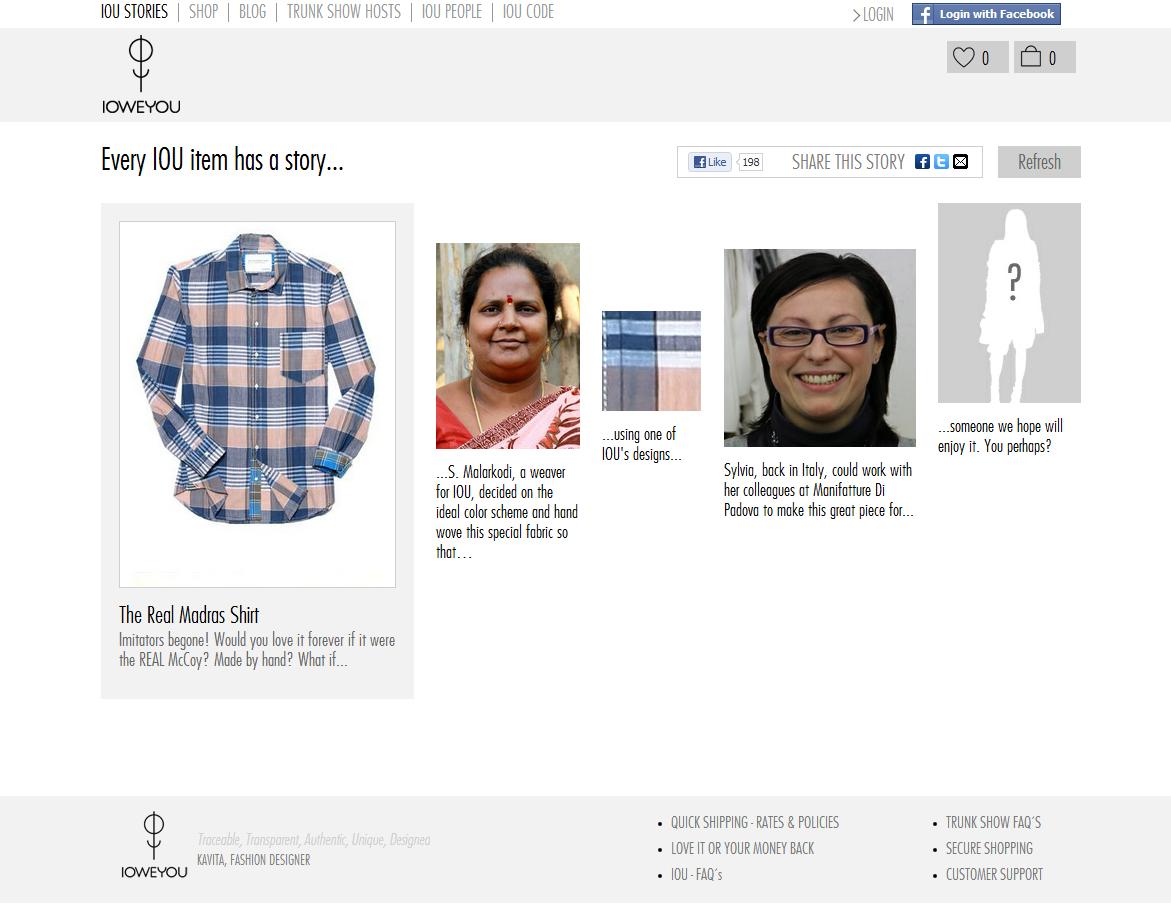

In essence, 3 approaches are widely available: Standardised reporting (such as ISO 26000); IT supported supply chain tracking (successfully used in e.g. Walmart’s fully traced jewellery line ‘Love, Earth’, the IOU project, or at Rapanui); and, very recently, a comprehensive 44 items ‘transparency’ questionnaire where all answers and supporting documentation will be made available in the public domain for critical stakeholder review.

Particularly supply chain tracking is, beyond transparency for the sheer sake of public reputation, is an interesting commercial tool and offers novel opportunities in marketing. Let’s name three of many.

Supply chain tracking – a marketing opportunity

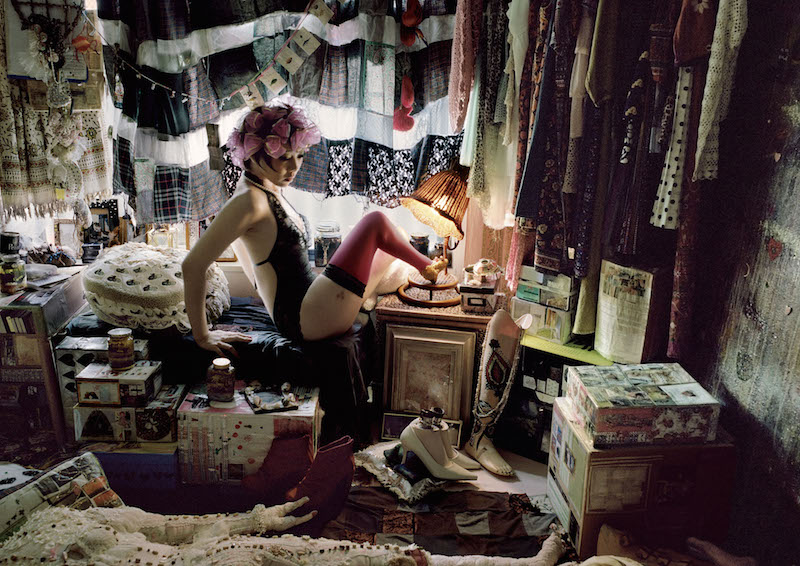

Via:http://iouproject.com/

1. Goods can be assured to be authentic.

Every component and work step that has gone into the making of a product (a bag, a pair of trousers, a ring) is tracked. Hence, it can be guaranteed that the product is authentic and not a forgery.

While the popularity of cheap fake brand products is proof of a brand’s value, brands are very keen to ensure that the ‘real’ product can be identified and distinguished from even the most accomplished of all forgeries. As a side-effect of supply chain tracking, this becomes possible.

2. Products get a unique personality and story.

With supply chain tracking, and the fact that each component, ingredient and process step is recorded, the product can be given ‘a personality’.

The consumer can get to know, for example, when a bag was produced, the cow whose hide was used, the artisan who worked the hide, and the location of the workshop or factory where the process took place. The details give the impression that even a mass-produced consumer good is a unique custom-made creation.

And let’s be honest: who doesn’t like to be the sole owner of a one off?

3. Customer relationship management.

By joining online memberships, consumers gain access to the story of the items, a bag or a pair of jeans, and, in return, businesses obtain a textbook opportunity to collect more detailed customer data: What is their age group? What other products of the same brand (old and new) do they own? What percentage of income do they spend on a product? The reality is a data protection authorities’ nightmare. Cleverly used, though, the opportunities for marketers that result from this type of data collection are endless. Armed with this degree of insight, personalised and targeted campaigns can finally be efficiently realised.

Conclusion

In the past, fashion companies may have agreed to meet voluntary standards, but often without much conviction or real commitment. Sometimes, the sole reason for participation was public relations. This applies notably, and very specifically to the fashion industry where calls for more transparency are old news, but are now finally backed up by an increasing number of consumers willing to pay more for their products if, and only if, they are guaranteed their money’s proper use.

From a consumer marketing perspective, traceable supply chains open the door to a dimension of information customisation and personalisation that so far has not been known or tested. From a one-on-one engagement with the customers over their individual purchases, to targeted marketing campaigns the potential of traceable supply chains, which are valuable for the transparency they provide, can only be imagined.