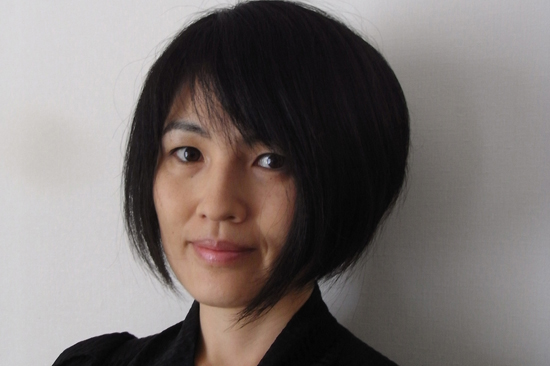

Designer Sara Arai started her prêt-a-porter line araisara in 2008, to express the connection between traditional oriental culture and fashion. Arai shows her collection at JFW since 2009-10A/W. She has been invited from several countries as Russia, India and Malaysia for express her fashion show abroad. She has joined Paris fashion week on schedule from 2013.S/S. to present Asian culture to the world from Japan.

―toki―

The present, a dot.

The past, a line.

The future, a shape.

A dot becomes a line.

A line a shape.

Without a dot, a line can’t be created.

Without a line, we can’t create a shape.

A dot in a moment.

A line in a moment.

A shape in a moment.

Everything linked together, in a single moment.

(translation: shirahime.ch)

Each moment is a dot, which will create a line, which will eventually form a shape. This was a collection theme as well as brand concept. Six years since the launch of my first collection, this principle still inspires me and makes me feel I need to cherish every moment of each day.

It was five years ago that one of my customers brought in a long Miyazome-dyed handkerchief. I remember falling in love with this beautiful dye. As soon as I could, I visited the Miyazome-dye atelier in Utsunomiya City in the northern Kanto region. It was run by just one man, who was 80 years old.

He follows the traditional recipe exactly, using water from the Tagawa River and, for dyeing materials, wild flowers picked from around the atelier and naturally air-dried with sunshine and wind. I could feel the soul of the artisan, how he cherished the ancient ingenuity of the creations.

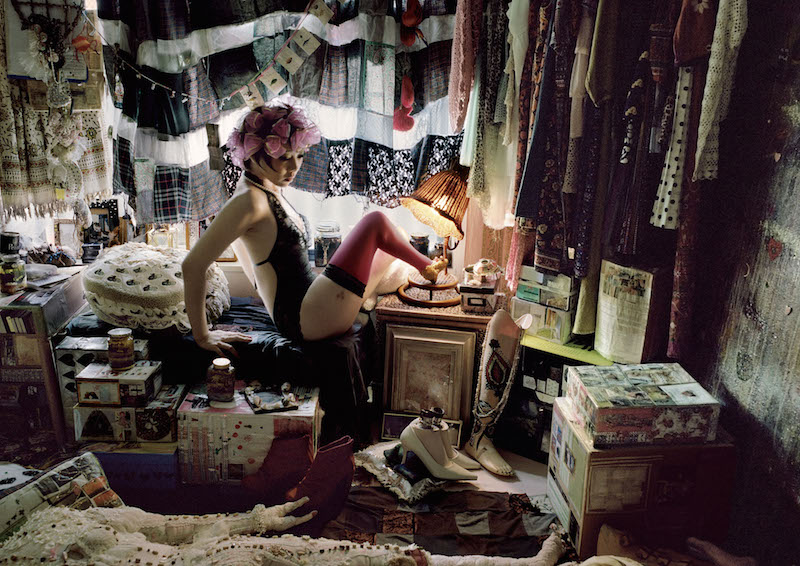

The colours come out differently according to how the sun has shone and the condition of the soil and flowers. When I saw some of the 15-meter long Miyazome-dye textiles in various colours blowing in the wind, it was like the pieces were dancing with light, joyful steps.

The artisan told me that Miyazome-dyes are becoming extinct as they are now used only for tenuguii handkerchiefs (an old style of Japanese handkerchief) or yukata. Therefore it is in little demand from customers, and there are no disciples learning the technique; when this artisan passes, the technique will vanish. While washing a newly dyed piece of cloth, he said to me,

There was once a time when Miyazome-dyes were so famous and popular that Utsunomiya was synonymous with them. But now, what people would have in mind when they hear the name Utsunomiya are Gyoza-Chinese dumplings. Even the locals don’t know of Miyazome-dyes. No wonder they are vanishing.

Finding this serene, natural place and the artisan, I realized what it means to live in nature; I also realized that I had to tell everyone about what we are losing.

As a clothes designer, I had some understanding of how the old techniques are gradually fading away, but I had my eyes shut, not recognizing how critical the matter is. Taking the easy way out by resigning myself to accepting this crisis would lead to the extinction of beautiful traditional techniques.

On my way back from Utsunomiya to Tokyo, I firmly resolved to follow my heart—I must pass on the wonderful traditional ways future generations through my clothes and tell more people about the beauty of Asian scenery, nature, and culture, and the Asian soul . In order to do that, we must determine what to preserve and what to change.

Therefore, I decided to participate in Japan Fashion Week (JFW) as a prêt-a-porter designer, so I could present my stories to as many people as possible. Working with haute-couture wear, I found that I could help individuals by making clothes that solve their problems. I also wanted to find a way to help people with prêt-a-porter wear.

With the contribution of great artisans, araisara presented its first collection during JFW in March 2009 with pieces featuring the Miyazome-dyes.

After the runway show, which received much applause, people said to me such things as “It was great!” “It touched my heart.” “Watching the models walk brought tears to my eyes.” When I heard these glowing reviews, I remembered the days with artisan, when the dots I had been tracing connected into a line, and these lines made my collections. I was sure I could pass on his techniques to future generations. In fact, some local schools in Utsunomiya have started classes for Miyazome-dyes, and some younger people have started to visit the factory—with some even working as apprentices after seeing my collection.

I would like to continue to carefully draw each dot of the moment and trace them to create new collections. It would be exciting if this article became a dot for you and led you to a new line for a new creation.

Miyazome-dye

This dye dates from the late Edo Period, when Mooka cotton (cotton produced in Mooka City, Ibaraki Prefecture, east of Utsunomiya City) became prosperous. Many artisans gathered around the Tagawa-river, which flows between Mooka City and Utsunomiya City, to dye the Mooka cotton textiles, which became known as Miyazome-dye. Dyed fabric produced in the Tagawa-river region is generically called Miyazome-dye.

Later, the artisans developed a method called chu-sen (a method of dyeing using mud to make a bank in the shape you want to create and then pouring the dye in) and started to dye the textiles with artistic designs.

It comes out just as beautiful on the front and back, so it could be said that there is no front or back. It is naturally dried on sunny days, preventing the filaments from being destroyed and making the fabric well ventilated.

The design changes as you use it, so you can enjoy the unique changes of your own piece.